Heart Surgery and Heart Transplants

Gibbon was one of the first to attempt the well-known cardiac bypass technique in the late 1930s using cats. In these early experiments, he tested various types of pumps and oxygenators. He developed an artificial lung based on a spinning hollow cylinder into which the blood was trickled. After World War II, Gibbon and his colleagues started extensive experiments in dogs to test the effects of the prolonged passage of blood through an artificial lung. Later they totally disconnected the heart and lungs from the circulation. Gibbon was able to overcome the problem of small clot formation by installing fine filters in the circuit. After refining the bypass operation technique, he was able to reduce mortality in the dogs to 12% by the early 1950s. He performed the first open heart operation using heart lung machines on human patients soon thereafter. The first successful operation was performed on an 18-year-old girl who had developed right heart failure due to an atrial septal defect. A 45-minute operation was performed to correct the defect; the patient made a complete recovery and was still alive and well many years later.

One of the problems encountered during these early operations was the fact that the heart continued to beat, causing leakage of blood and presenting the surgeons with the difficult task of working on a moving object. Experiments with dogs, rabbits and rats established that potassium citrate could be used to safely arrest the heart and that cold cardioplegia would protect it in this state. The replacement of heart valves, too, was developed in dogs, rabbits, guinea pigs and rats, and minimally invasive surgery was developed in young pigs that were used to test the suturing of bilioenteric anastomoses, which conveyed bile satisfactorily after ligation of the common bile duct.

Michael DeBakey, probably the world’s most famous heart surgeon, was one of the first to operate on the heart, performing 60,000 operations over a span of 70 years with exceptional skill and judgement. He operated on numerous world leaders, including presidents John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard Nixon, as well as Boris Yeltsin, the Duke of Windsor, King Hussein of Jordan, the Shah of Iran and stars such as Marlene Dietrich. He was a pioneer in numerous fields: pumps for heart-lung machines, coronary artery grafting, blood vessel repair and the famous artificial heart that he developed together with another giant of surgery, his student Denton Cooley.

All the developments of DeBakey and his students were based on animal experiments. They worked above all on dogs and calves, even though DeBakey himself had several dogs in his home as pets. It is impossible to count DeBakey’s honors or even the number of university buildings or surgical instruments that carry his name.

The “human surgeon” DeBakey passionately campaigned for animal experimentation. He didn’t charge his super-rich patients, who included Aristotle Onassis and Stavros Niarchos, but asked them instead to donate to the Foundation for Medical Research, which promotes animal experiments. The foundation donates 2 million US dollars annually to Baylor University and also funds the DeBakey Journalism Award, which highlights the benefits of animal research.

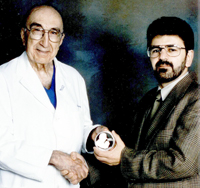

During his time at Baylor College of Medicine, Nikos Logothetis was honored with the DeBakey Award for Excellence in Science for his research in monkeys aimed at better understanding the neural mechanisms of visual perception. The award was presented to him by Michael DeBakey himself. Looking back, Logothetis says, “I vividly remember his human warmth, his enthusiasm for our research and his great interest in brain science. The opportunity to meet such people has always been a great inspiration to me. When I think of their enormous contribution to the health and well-being of mankind and their dedication to science and the responsible use of animals in research, it makes me sad to see the thoughtless and short-sighted fanaticism of some animal research opponents.”